Welcome back to THG recommendations after a while.

Let’s begin this post with a brief yet comprehensive video from The Economist:

Looking for a passionate yet objective assessment of what is really going on in China economically? You should not miss this interview with Dan Wang by Noah Smith:

Some highlights:

I think there has been a consistent pattern of Chinese successes and failures. Any technology that demands the complex integration of different scientific areas is challenging for Chinese firms. Semiconductors bring together electrical engineering, chemistry, computer science, and more; aviation is the integration of aerodynamics, materials science, mechanical engineering, etc. China's scientific capabilities have steadily risen, but I would say it's still fairly weak. No surprise, perhaps, that Chinese firms weren't able to produce mRNA vaccines, since its scientific establishment is unused to puttering around the fringes of new fields.

On the other hand, for any technology where the science is mature, and the complexity lies more with the manufacturing process, China tends to be strong. Take renewable technologies like solar photovoltaics or EV batteries. The science of turning light into electricity and power storage are pretty well understood. But Chinese firms have been able to outbuild their foreign competition (with plenty help from government support) in creating high-performing products. Putting together a battery, for example, involves around ten steps—from cell filling to final sealing—that demand perfect handoff at each stage. Chinese firms are really good at this, which they learned from the highly-demanding electronics supply chain.

And this:

…. And scale always helps to bring down the cost curve. I understand that the largest Foxconn facilities today have around 300,000 people, producing iPhones around the clock in three shifts per day. By contrast, the largest facilities in India are still closer to 30,000 people, for reasons that include less mature infrastructure and a lower female labor force participation rate. Manufacturers are able to gain so much in efficiency when they have more workers by one order of magnitude.

About the future of freedom in China:

…. But I have two questions for the future. First, how easily will Beijing decide to re-impose these restrictions for other crises? China's leaders don't always exercise restraint once they know they have a useful tool for social control. Second, what will the neighborhood committees do with their newfound powers? The paper by An and Zhang make clear that local authorities are the most disliked level of government: can they stop themselves from causing greater discontent?

If social aspects of life in China fascinate you more than economic or political ones, there is a podcast you cannot miss: Drum Tower from the Economist. Here is a particular episode I’d strongly recommend:

The story of Kong Yiji, a miserable scholar-turned-beggar, written by Lu Xun in 1918 has gone viral among young Chinese. A record 11.6m of them are expected to graduate from university this year, but the unemployment rate for people aged 16 to 24 in cities is nearly 20%.

The Economist’s Beijing bureau chief, David Rennie, and senior China correspondent, Alice Su, discuss why the story of Kong Yiji has caused an argument between Chinese netizens and the state. They also hear from graduates about how they see their job prospects.

Wondering which debates are raging in China from the gender perspective? You may read this tragic story of a woman who was trafficked/bought in 1998 for 5000 Yuan and was then chained like an animal for decades giving birth to eight children from her ‘husband’ in captivity.

For the historical context of the current developments in China, you may check out these two articles (one yesterday’s guest post and one old recommendation):

Francesco Sisci: China has Trade Surplus. It Also Has Suicide Chat Groups. Are The Two Related?

Guest post by Francesco Sisci first carried by Settimana News as China’s Suicidal Surplus. Published here with author’s permission. (Please keep tuned for a THG recommendation post focusing on China that will follow shortly.) Francesco Sisci (Image courtesy: Sisci’s Twitter account)

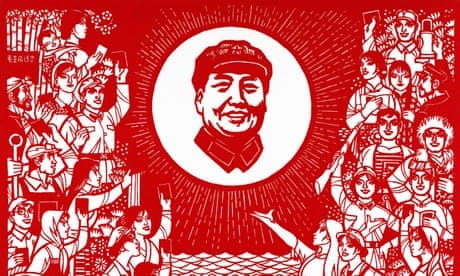

Human Impulses Run Riot: China's Shocking Pace of Change by Ya Hua, The Guardian (2018). Also available as podcast with same title:

In my 58 years, I have experienced three dramatic changes, and each one has been accompanied by a surge in suicides among officials. The first time was during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966. At the start of that period, many members of the Chinese Communist party woke up one day to find they had been purged: overnight they had become “power-holders taking the capitalist road”. After suffering every kind of psychological and physical abuse, some chose to take their own lives. In the small town in south China where I grew up, some hanged themselves or swallowed insecticide, while others threw themselves down wells: wells in south China have narrow mouths, and if you dive into one headfirst, there is no way you will come out alive.

In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, many people from the lowest tiers of society formed their own mass organisations, proclaiming themselves commanders of a “Cultural Revolution headquarters”. These individuals – rebels, they were called – often went on to secure official positions of one kind or another. They enjoyed only a brief career, however. Following Mao’s death in 1976, the subsequent end of the Cultural Revolution and the emergence of the reform-minded Deng Xiaoping as China’s new leader, some rebels believed they would suffer just as much as the officials they had tormented a few years before.

Thus came the second surge in suicides – this time of officials who had clawed their way to power as revolutionary radicals. One official in my little town drowned himself in the sea: he smoked a lot of cigarettes first, and the stubs littering the shore marked the agony of indecision that preceded his death. This was a much smaller surge in suicides than the first one, because Deng was not out for political revenge, focusing instead on kickstarting economic reforms and opening up to the west. This policy led in turn to China’s economic miracle, the downside of which has been environmental pollution, growing inequality and pervasive corruption.

In late 2012 came the third dramatic change in my lifetime, when China entered the era of Xi Jinping. No sooner did Xi become general secretary of the Communist party than our new leader launched an anti-corruption drive, the scale and force of which took almost everyone by surprise. The third surge in suicides followed. When officials who had stuffed their pockets during China’s breakneck economic rise discovered they were being investigated and realised they could not wriggle free, some put an end to things by suicide. In cases involving lower-ranking officials who were under investigation but had not yet been taken into custody, the government explanation was that their suicides were triggered by depression. But, if a high-ranking official took his own life, a harsher judgment was passed. On 23 November 2017, after Zhang Yang, a general, hanged himself in his own home, the People’s Liberation Army Daily reported that he “had evaded party discipline and the laws of the nation” and described his suicide as “a disgraceful action”.