The shadow war is over. Iran’s direct attack on Israel, with its own missiles from its own territory opens a new chapter in Middle East power politics. It is the realization of a nightmarish confrontation. It will no doubt trigger a reset in global confidence and expectations about geopolitical risk.

Within the Iranian regime, as Nicole Grajewski points out, the attack has involved a new and high profile role for the “IRGC Aerospace Force (IRGC-AF) - a lesser-known branch of the IRGC than Qods. Led by Brigadier General Amir Ali Hajizadeh, the IRGC-AF is likely lobbying for a response that showcases Iranian ballistic missiles.”

But over the last few days we have also seen a play of “diplomatic” forces in the region that suggests that the risk of general conflagration is being very self-consciously managed. A great account to follow on all of this is Gregory Brew who is deeply knowledgeable about Iran and the region.

Iran escalated, but seems to want to escalate-to-deescalate.

In Israel Netanyahu may have every interest in escalating, and he has folks like Ben-Gvir in his cabinet who are calling for a “beserk” reaction. But others, notably Gantz, are signaling a more measured response.

Biden appears to have told Netanyahu that he will not support tit-for-tat escalation v. Iran. The official white house read out from their conversation highlights Iranian attacks on military facilities in Israel, limiting the scope of outrage politics.

As Suzanne DiMagio points out, back channel diplomacy between the US and Iran is actually working quite well.

Turkey and Iraq appear also to have been very much in the loop. In a truly astonishing turn of events, Jordan and Saudi Arabia appear to have been roped into the missile defense alliance against Iran’s well-telegraphed attack.

So, the reading currently favored by most economic commentators and the folks who have to deploy trillions of dollars on Monday morning, is that though this escalation is alarming, it is an example of the key players successfully signaling that they “have to act”, but seeking to avoid general escalation.

If true, this would be good news. It could lead to a muted market reaction next week diminishing the shock. But, at the very least, the escalation of tension in the Middle East combined with growing anxiety about Ukraine demonstrates once again how significant “the geopolitical downside” is, right now. So where does the world economy go next? Below some useful pointers for your Sunday reading.

**

For the economy, the most obvious question is what happens to oil prices? The go-to source on all things commodities, is Javier Blas at Bloomberg Yes this costs $, but good news coverage does and Blas alone is worth the price of entry. I am going to use his most recent column as a spine for this collection of material.

The shock of this weekend comes against a backdrop in which OPEC was pursuing a goldilocks strategy i.e. getting the oil price “just right”. Not too low. Not too high!

$99.99 oil?

Recently, I (Blas) asked the head of a state-owned oil company in the Middle East what price OPEC+ is aiming for. Laughing, he replied: $99.99 a barrel, and not a single cent higher. Even following Iran’s missile attack on Israel, there’s a good chance the cartel can keep crude prices below the triple-digit barrier. My interlocutor was intentionally flippant, but directionally, his assessment sounds about right. Yet, on any given day, achieving oil prices that are neither too hot nor too cold is extremely difficult. The geopolitics of the Middle East only confuses the calculus and makes it almost impossible to reach the fabled goldilocks level.

For historical context, the current level of oil prices, once adjusted for inflation is elevated but not dramatically so.

So where do we go from here. Blas cites the following considerations:

Oil is still flowing. Straits of Hormuz so far unaffected. This is THE big issue. 18 million b/d of oil flows through the Persian Gulf - c. 18% of global demand. Unlike the Red Sea, there are no alternative routes. If this is at risk in any serious way. the impact on oil markets will be dramatic. So far there is little evidence of serious escalation. So far.

Risk of major disruption has clearly increased, but this likely be reflected in options market most directly.

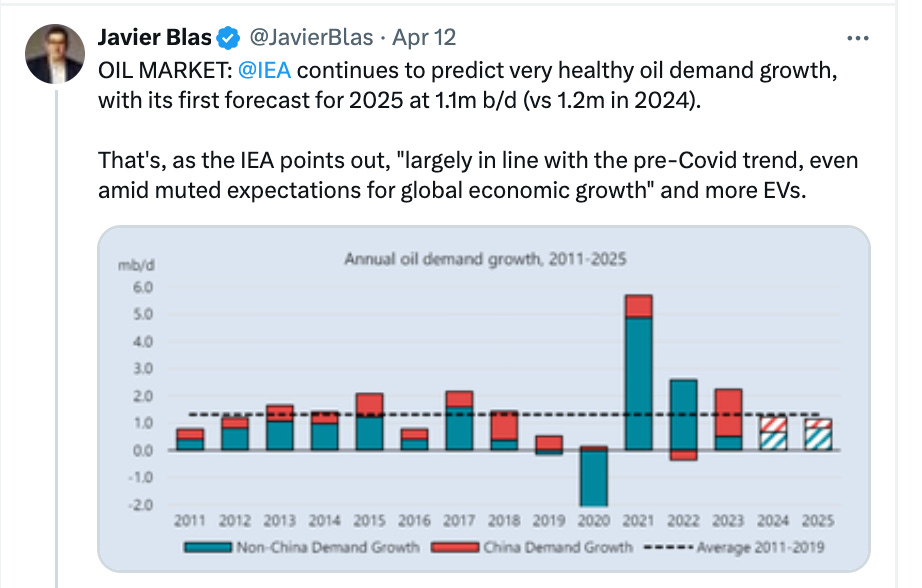

Even before the shock there was every reason to expect the balance in the market to shift towards higher prices. Oil demand is set to grow relatively strongly in 2024. Inventories will likely fall unless OPEC countersteers.

See also Cahill and Alkadiri at CSIS

China’s demand growth is widely expected to slow this year after an exceptionally strong 2023 as post-Covid travel subsides and its economy slows, but Chinese petrochemicals demand remains robust. And both India and the Middle East will support demand.

OPEC+ has been keeping supply tight. But since April there have been signs that they are likely to agree to increase supply at June 1 meeting. It may choose to keep market guessing by calling monthly meetings and slowly increasing.

There is plenty of spare capacity. Saudi, Emirates and Iraq are keeping 5 m barrels per day off global market = 5% of world demand and more than Iran produces. Only an actual military interruption to Gulf flow threatens a serious shortage.

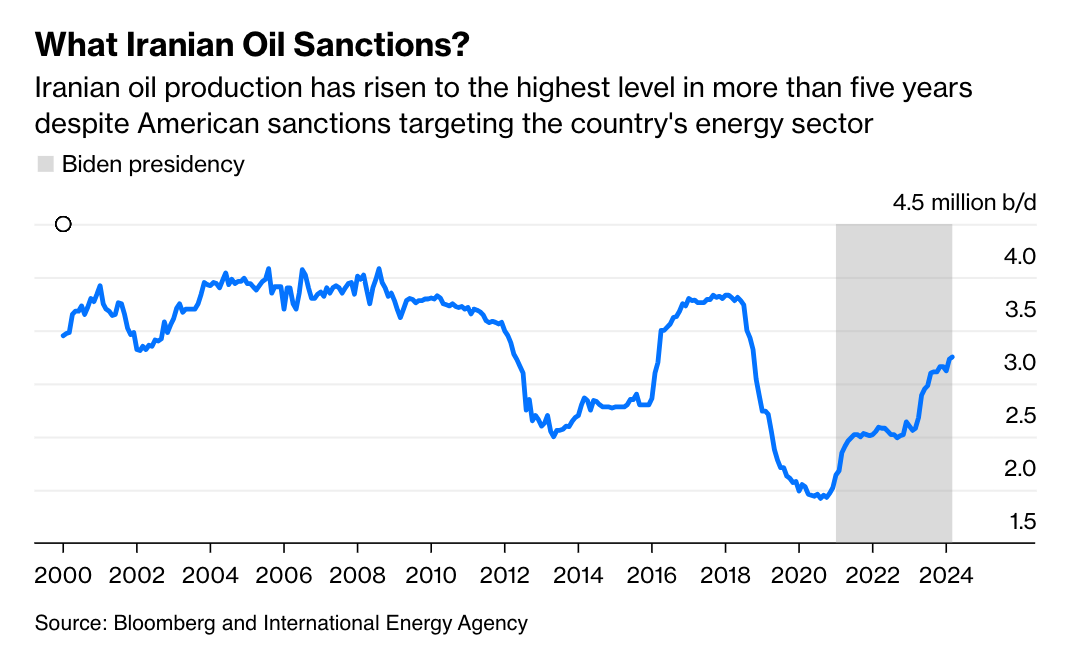

Short of military escalation in gulf itself, the main risk to global supply is possibility that Biden admin may reverse de facto loosening of sanctions on Iran and lock 1.5 m tons per day out of the market. Will Biden take that risk in an election year?

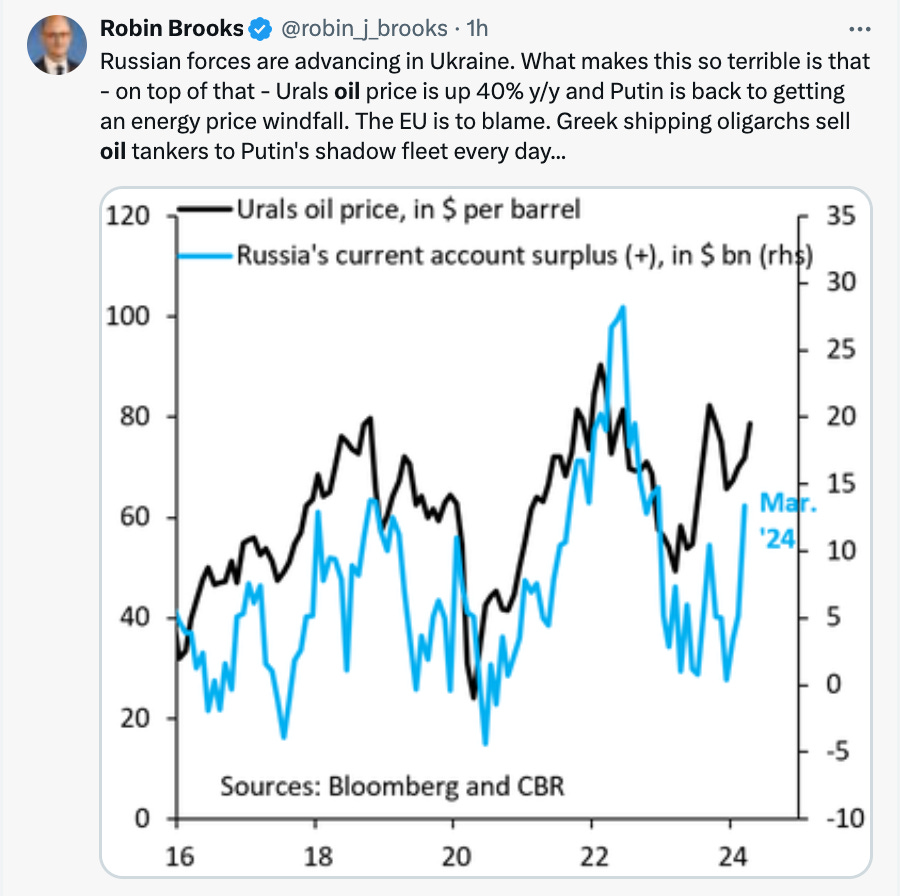

Russia is a major beneficiary of any shock to global oil supply. It is currently selling oil well above the notional G7 $60 per barrel sanctions cap. Biden admin will have to weigh this.

On this Robin Brooks has been sounding the alarm

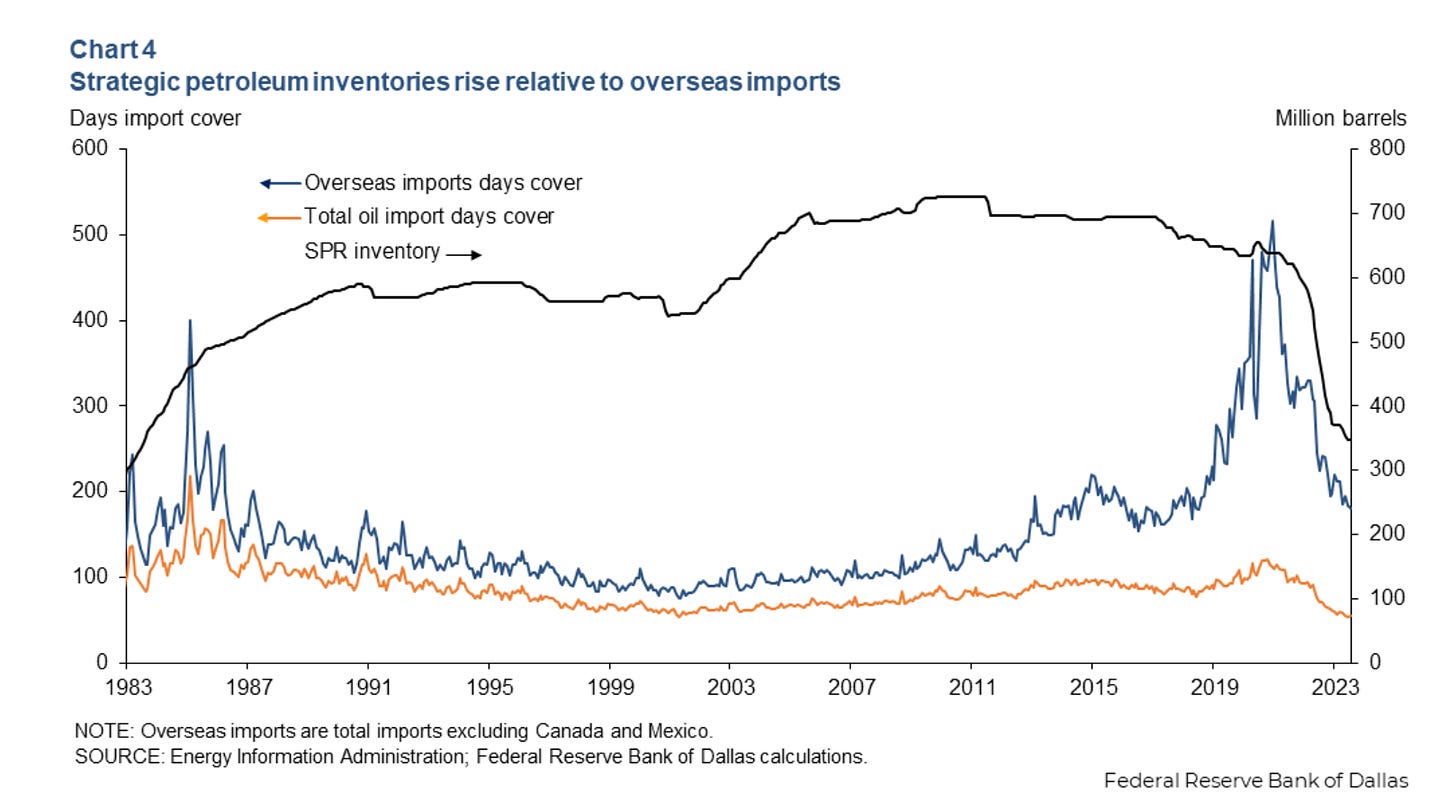

If OPEC does push for goldilocks $99.99, Biden may be tempted, as election approaches, to deploy the 365 m barrels that the USA has in its strategic petroleum reserve (half its former level) but still enough to move the market. The administration is clearly worried about the price level and is conscious of the role the SPR plays. As Cahill and Alkadiri point out the administration recently canceled its latest solicitation to help refill the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), not wanting to further stoke demand and drive prices.

As the Dallas Fed analysis shows, measured relative to the IEA standard of net imports the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve is more than adequate. The US is now a major net exporter of oil. Relative to gross imports, allowing for fact that the US imports different varieties of oil, the cover ratio is rather lower.

Far from refilling the tanks, the Iran-Israel could potentially provide political cover for the Biden administration to engage in further sales, thus moderating upward price pressure.

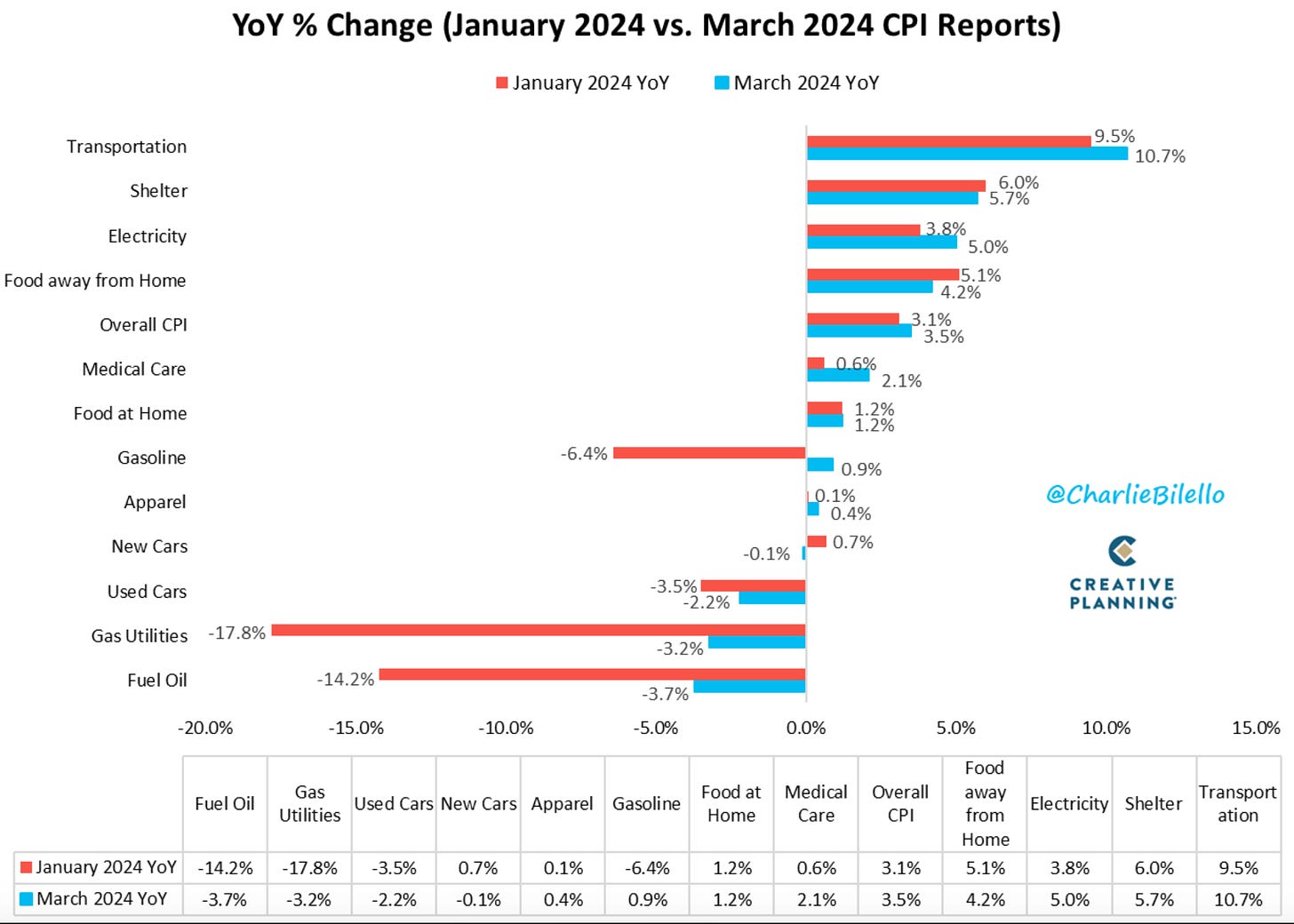

Petrol prices reversing direction and heading upwards, added significantly to the nasty inflation bump in the USA in March, which is both bad for Biden politically and has reversed market expectations about the direction of Fed policy.

For the “Rest of the World”, unless you are an oil exporter, this constellation is definitely bad news.

You face the prospect of higher oil prices, which nowadays tend to correlate with a strong dollar, in which you may have borrowed, or may want to borrow, or may have to use to buy imports.

You face the prospect of a Fed more worried about inflation and likely to hold interest rates higher for longer or even raise.

As Gita Gopinath of the IMF has been arguing, along with all the key folks at the BIS: a strong dollar is bad for the global economy.

In major EM this pressure is felt, as I learned first hand in Brazil last week.

Juntaro Arai at Nikkei has a good piece describing the impact on the wider world of recent shifts in market expectations about Fed policy. After this weekend all of the below will need to be underlined.

Countries across the globe are becoming increasingly wary of the growing might of the U.S. dollar. Emerging economies such as Indonesia have begun to move to defend their currencies against the possibility of renewed inflation and downward pressure on growth through higher import prices. The negative impact of the dollar's predominance on the global economy is likely to be one of the main themes at the Group of 20 of meetings finance ministers and central bank governors, which opens on Wednesday in Washington. The currencies of G20 countries are almost all depreciating against the dollar. The decline since the beginning of the year has reached 8% for the yen and 5.5% for the South Korean won, led by the Turkish lira at 8.8%. Both developed and emerging economies have seen currencies weaken at an accelerating pace, with the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, and euro falling 4.4%, 3.3%, and 2.8%, respectively, in developed economies. … Governments are increasingly concerned about the falling value of their currencies. Emerging economies are particularly sensitive to the negative effect, as the burden of dollar-denominated debt increases along with larger interest expenses due to higher rates. … Several countries have already begun to take actions. On April 1, Brazil's central bank intervened in the foreign exchange market for the first time since President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva took office. Although the government and the central bank have not clearly explained their intentions, some in the market believe that the purpose is to correct the depreciation of the real. Several local media outlets report that Bank Indonesia also decided to intervene in the currency market this month. The objective is to correct the level of the rupiah, which is at a four-year low. But the rupiah has been on a downward trend since those reports, falling beyond the milestone level of 16,000 rupiah to the dollar. According to Reuters, Bank Indonesia Gov. Perry Warjiyo made a statement at the end of January that was intended to check the currency's depreciation. The central bank has taken steps to intervene, but they have not been fully effective. Turkey's central bank raised its policy rate by 5% to 50% in March in response to the lira's depreciation and accelerating inflation. … "We are feeling a bit more hawkish than before," Eli Remolona, the Philippine central bank governor, said recently, citing the higher risk of inflation. … These concerns are not just limited to developing economies, Japan and other developed countries are nervous about the incessant depreciation of their currencies. Speaking about the upcoming G20 meeting, Japanese Finance Minister Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki said Friday that "it is possible that [the dollar] will be on the agenda. We have discussed capital flight before."

As usual, in the face of a shock like this, it is the weaker players that feel the shock most acutely and that bear the brunt of the pain.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails full of great reading, links and images, several times per week.